Beyond the Drill: Redefining Ethics in Dentistry

By Katelyn Nguyen

Ethics in dentistry touches every treatment plan and chairside conversation. It shapes how schools train students, how teams navigate gray areas in clinic, and how providers match care to what patients want and need. At UNC’s Adams School of Dentistry, third-year dental student Jennifer Judd is pushing that conversation forward. She is the principal investigator of an ongoing national study on ethics education in U.S. dental schools and an advocate for teaching ethics as an intentional, value-driven practice.

Headshot of Jennifer Judd

Judd’s path blends early exposure to clinical care with a growing passion in philosophy. Years of orthodontic treatment as a kid sparked her interest in dentistry, and her senior year of high school opened the door to ethics and philosophy. When she arrived at UNC in 2020, she immersed herself in the Parr Center for Ethics. She collaborated with the National High School Ethics Bowl to explore applied ethics in depth. At the same time, she began her journey into dental research under the guidance of orthodontic-scientist Dr. Laura Jacox in the Jacox Lab at the Adams School of Dentistry. Judd gained knowledge of research fundamentals, Institutional Review Board (IRB) processes, and mentorship that would later make independent work possible.

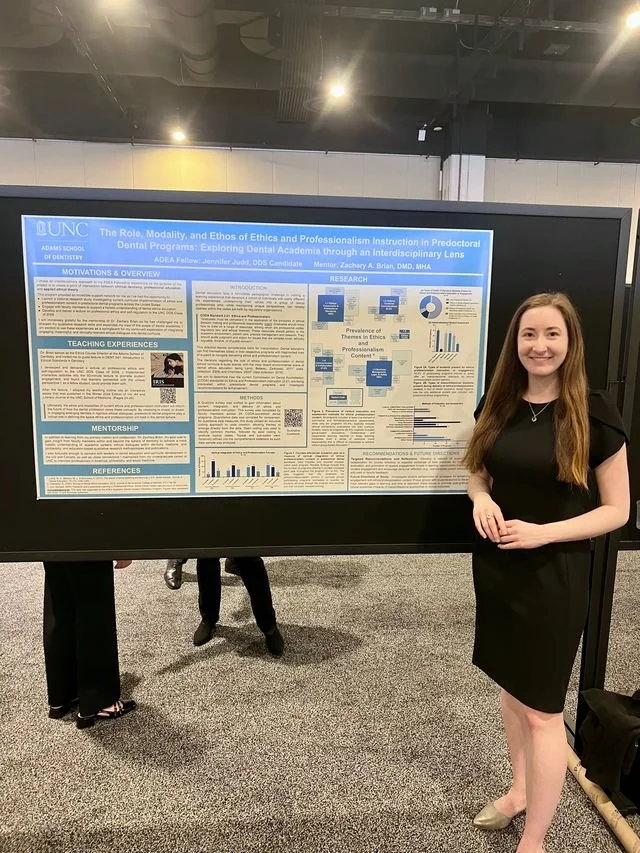

Dental ethics presents its own distinct clinical realities and dynamics, and, as an ethics researcher, she noticed a gap. “I started to realize that dental ethics wasn’t really a developed field‒most of our concepts are pulled directly from medical ethics. While we are all healthcare professionals, I think there are some unique features to the dental profession that require context-based conversations that diverge from medicine,” stated Judd. To explore this in her upcoming manuscript, Judd set out to understand how dental schools interpret the Commission on Dental Accreditation's ethics requirement, known as Standard 2-21. A key collaborator Dr. Zachary Brian, a health policy professor at the Adams School of Dentistry, worked with Judd as she conducted an IRB-approved survey using Qualtrics, targeting instructors to find out what content they teach, how it is integrated into their curriculum, and the methods of instruction they use. His expertise in synthesizing large volumes of qualitative data pushed the project ahead as Judd combined quantitative summaries with qualitative analysis through an inductive codebook to uncover themes that numerical data alone may not reveal. To facilitate this, she compiled a list of public faculty contacts from all CODA-accredited programs, ensuring she reached the individuals responsible for ethics education.

Judd’s aim is pragmatic. Before proposing reforms, the field needs a current baseline. Prior national surveys are dated, and many programs have reworked curricula since then. Her working hypothesis is that Standard 2-21 leaves wide room for interpretation. “It’s in danger of being too vague for a topic as critical as dental ethics and instruction for professional behaviors. As a profession, we should want to ensure students understand the technical aspects of dentistry, but also how to think critically and behave professionally in clinical situations,” Judd expresses. Her early conversations with educators point to a fragmented landscape where powerful teaching ideas rarely travel between schools. Teaching is central to Judd’s vision. Through the ADEA Dental Academic Careers Fellowship with Dr. Brian, she delivered a first-year lecture on dental ethics and professional self-regulation and is returning to teach it again. In both the lecture and her essay “Deconstructing the Idea of Ethics in Healthcare” published in Iris, UNC School of Medicine’s arts and literary journal, she reframes ethics as a pattern of mindful action rather than a checklist of rules. She invites learners to examine core values and argues that providers must understand how life experience calibrates their intuition so they can deliver care aligned with patient needs, not just professional instincts. In a case with an older patient who had significant sensory and mobility limitations, the textbook path would have aimed for comprehensive crown work. The patient’s priorities were different, however, and function mattered more than aesthetics. For Judd, ethics lives in that pivot from an idealized plan to the plan that best fits the person in the chair. Her upcoming manuscript grows from this philosophy. It treats ethics education as a design problem. Lectures alone are insufficient. Discussion, cases, team-based work, clinical observation, and feedback tied to professionalism need to be routine because Judd believes that “you cannot become a more ethical person just by reading philosophy. As a healthcare professional, you have to be out in world, you have to make mistakes, and you have to interact with colleagues and patients.”She is particularly interested in creating assessment tools for ethical and professional development that any program could adapt into its curriculum.

Judd Presentation at Dental Ethics Research at the 2025 American Dental Education Association Annual Conference

If institutions can measure students’ ethical competency in consistent ways, faculty can see what works, iterate faster, and share practices across programs. Many students will enter clinical careers where ambiguous cases are common and time is short. Ethics training that builds habits of reflection and collaboration can prepare us to make better decisions for people whose lives do not fit textbook templates. Ethics does not sit apart from dentistry; it is the framework that holds up every treatment plan and chairside conversation. Judd’s work reminds us that better habits can be taught, measured, and improved. The result is dental care that is more thoughtful, more transparent, and more aligned with what patients truly need and value.